The belief that we must choose between digital and physical archiving is a false dichotomy; true preservation lies in actively managing the inevitable decay inherent in all formats.

- Digital media suffers from “bit rot” and format obsolescence, while physical artifacts face predictable chemical degradation.

- The greatest risk isn’t material loss, but the loss of context, which erases an object’s meaning and historical value.

Recommendation: Cultural institutions must shift from a passive storage mindset to a dynamic strategy of “managed decay,” focusing on continuous data migration, contextual integrity, and conscious selection to preserve meaning, not just matter.

The central question for every historian, archivist, and cultural institution is one of permanence. In the quest to secure our collective memory for the next century, we are presented with a seemingly straightforward choice: the tangible resilience of physical artifacts versus the boundless accessibility of digital surrogates. The debate often frames paper, canvas, and film as stable but fragile islands, while digital files are seen as infinitely replicable yet treacherously ephemeral. This binary view, however, obscures a more profound and unsettling truth.

The common wisdom advises us to digitize everything, creating backups and storing them in the cloud. Yet, this approach ignores the insidious nature of digital decay and the biases inherent in what we choose to preserve. The real challenge is not a simple matter of selecting the right hard drive or acid-free box. It is an ongoing philosophical and technical battle against informational entropy—the universal tendency for order and meaning to dissolve into noise. What if the core of preservation is not about preventing decay, which is inevitable, but about actively managing it?

This article reframes the archival challenge. We will move beyond the superficial “digital vs. physical” debate to explore the deeper forces that threaten our heritage. We will investigate why digital data can degrade faster than ancient paper, the ethical dilemmas of access and selection, and the critical importance of context over content. The ultimate goal is to build a new framework for preservation, one that accepts decay as a constant and focuses on what truly matters: securing the meaning of our history for generations to come.

To navigate this complex terrain, this article is structured to address the most critical questions facing archivists today. The following sections will guide you through the technical, practical, and ethical dimensions of long-term preservation.

Table of Contents: The Enduring Challenge of Archival Permanence

- Why “Bit Rot” Destroys Digital Art Faster Than Paper Fades?

- How to Create Digital Twins of Sculptures for Remote Study?

- Open Access or Copyrighted: Which Model Best Serves Cultural Heritage?

- The Selection Bias That Erases Marginalized Cultures from Archives

- Creating a Disaster Priority List: What to Save First in a Fire?

- Cloud vs. Hard Drive: Which Storage Lasts Longer than 10 Years?

- Why Traditional Varnish Turns Yellow on Renaissance Paintings?

- Separating Artist Biography from Artwork: When Does Context Matter?

Why “Bit Rot” Destroys Digital Art Faster Than Paper Fades?

The term “bit rot” sounds like a quaint technical glitch, but it represents a fundamental principle: informational entropy. Unlike paper, which fades through predictable chemical processes, digital information exists in a binary state. A single flipped bit can render an entire file unreadable, causing a catastrophic loss of information. This degradation can occur silently on magnetic or flash storage media due to environmental factors, cosmic rays, or simple material decay. The problem is not that digital is fragile, but that its failure is often absolute and silent until it’s too late.

The fragility of digital formats is an accelerating crisis. According to a recent analysis, the risk to our digital legacy is growing, not shrinking. A report from the Digital Preservation Coalition found that in 2024, six digital categories showed increased risk of being lost, with no corresponding decrease in risk for any category. This trend highlights that our capacity to generate data far outstrips our ability to secure it. Beyond bit rot, the constant evolution of hardware and software means that a perfectly preserved file can become a digital fossil, unreadable by modern systems—a phenomenon known as format obsolescence.

Case Study: NASA’s Lost Climate Data

A stark illustration of this challenge comes from NASA. Scientists attempting to access decades-old climate data discovered that 70% of the magnetic tapes containing these critical measurements were unreadable. The magnetic media had degraded, and the hardware to read them was obsolete. A massive recovery project costing $15 million was launched, but it could not reverse the entropy entirely; after years of effort, 30% of the original observations were permanently lost to decay, leaving an irreparable gap in our scientific understanding of climate change.

This points to a crucial distinction: physical objects often decay gracefully, retaining partial information, whereas digital objects face a “cliff of loss.” A faded manuscript is still legible; a corrupted JPEG is often just noise. Therefore, digital preservation cannot be a passive act of storage; it must be an active, continuous process of monitoring, migrating, and verifying data integrity.

How to Create Digital Twins of Sculptures for Remote Study?

In response to the fragility of physical artifacts and the need for global access, institutions are increasingly creating “digital twins”—high-fidelity 3D models of objects like sculptures. This process, known as digital surrogacy, moves beyond simple photography to capture the form, texture, and even material properties of an object. The primary technologies used are photogrammetry, where hundreds of overlapping photos are stitched together by software, and structured-light or laser scanning, which measures millions of points on an object’s surface to create a precise point cloud.

This technological push is a major focus of digital heritage efforts. As highlighted by recent studies, digital cultural heritage research focuses on three key areas: the development of interactive VR/AR experiences, the construction of comprehensive databases for cultural relics, and the creation of multimedia guides. The digital twin sits at the nexus of all three, serving as the foundational data asset for research, education, and virtual exhibitions.

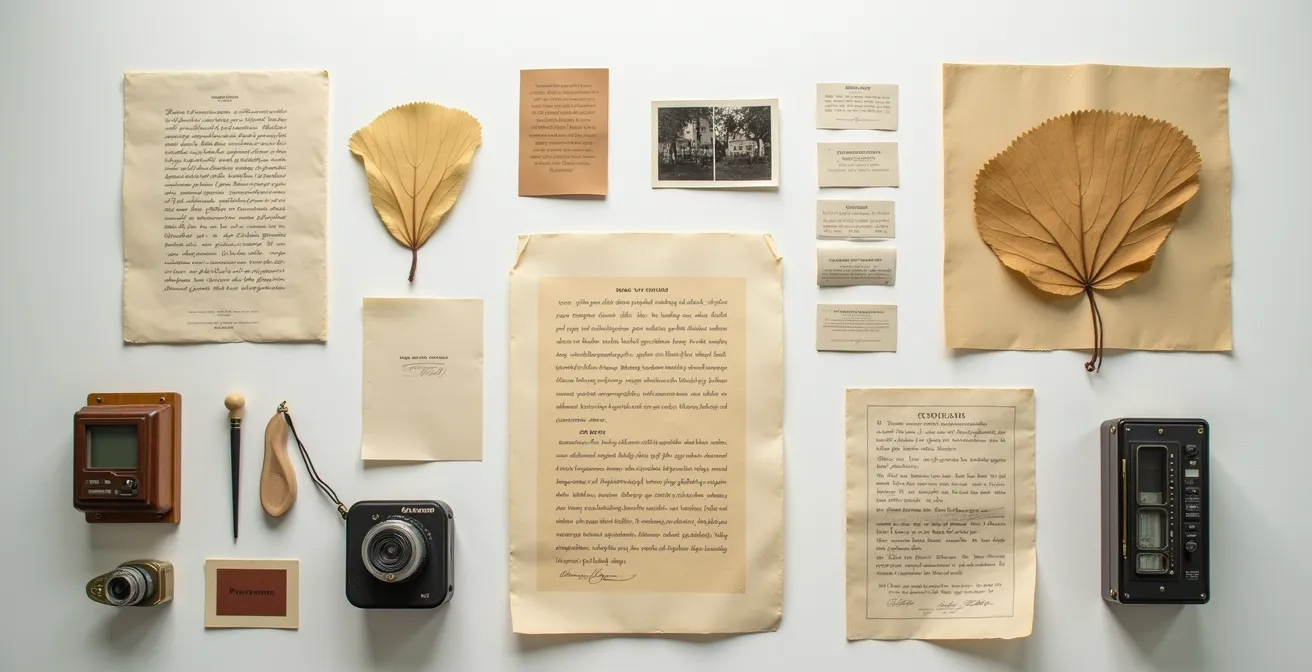

As the image illustrates, creating a true digital twin involves capturing data at a microscopic level. The goal is to produce a model so accurate that scholars can study chisel marks, surface erosion, or tool paths remotely, without risking damage to the original object. However, this raises a philosophical question: is this digital surrogate the object, or merely an interpretation? It lacks the original’s materiality, its weight, its smell, and its presence in physical space. While it provides unprecedented access to form, it can never fully replicate the object’s entire context and auric presence.

Therefore, creating a digital twin is not an endpoint but a starting point. The value of the model depends on the quality of its capture, the richness of its associated metadata, and the platforms through which it is made accessible. It is a powerful tool for study, but a tool that must be understood as a representation, not a replacement.

Open Access or Copyrighted: Which Model Best Serves Cultural Heritage?

Once a cultural artifact is digitized, a critical ethical question arises: who owns the copy, and who gets to see it? The two prevailing models, open access and copyrighted control, represent a fundamental tension between the goals of preservation and dissemination. Open access advocates argue that cultural heritage is a public good; digitizing it with public or institutional funds implies a responsibility to make it freely available to all, fostering research, education, and creative reuse.

Conversely, many institutions rely on licensing high-resolution images to generate revenue, which in turn funds further preservation and curatorial work. Furthermore, copyright law itself presents a maze of complexities. As the Digital Preservation Coalition notes, the legal status of digital materials is a significant barrier to preservation and access.

Copyright, intellectual property, and orphan works remain critical issues for many digital materials, not least in the world of video games.

– Digital Preservation Coalition, The Bit List 2024: Global List of Endangered Digital Species

This legal ambiguity often forces institutions into a cautious stance. To balance these competing interests, a hybrid approach is becoming standard. Many museums are now implementing tiered access models. In this system, low-resolution images are made available under open-access licenses for general public use, while high-resolution, publication-quality files are kept behind a paywall or require a specific license agreement. This model attempts to serve both the public good and the institution’s financial sustainability.

However, this solution is not without its critics. It creates a digital divide, where only well-funded researchers or institutions can access the highest quality data. The decision of where to draw the line—what resolution is “good enough” for the public—is subjective and can perpetuate inequalities in the scholarly world. The debate over access is not merely logistical; it is an ethical deliberation about the purpose of cultural memory itself.

The Selection Bias That Erases Marginalized Cultures from Archives

Archiving is never a neutral act. Every decision to preserve an object is also a decision to let another one fade. This process is shaped by selection bias, where institutional priorities, funding sources, and the conscious or unconscious-cultural values of archivists determine what is deemed “historically significant.” For centuries, this has meant that the histories of dominant, literate, and powerful groups have been meticulously preserved, while the heritage of marginalized, oral, and colonized cultures has been ignored, devalued, or actively erased.

Digital archiving has the potential to either amplify or challenge this bias. On one hand, the sheer cost and technical expertise required to digitize can lead institutions to prioritize their “masterpieces,” further cementing the traditional canon. On the other hand, digital platforms offer a powerful tool for counter-archiving. Social media and community-led projects can create new repositories of history that exist outside of formal institutions.

Research on the social archiving of intangible heritage, for example, shows how platforms like YouTube are becoming informal archives for cultural practices. User-generated content often provides richer, more diverse representations of traditions than official records, challenging institutional definitions of authenticity and value. These grassroots archives preserve the lived, evolving nature of culture, not just its static, museum-quality artifacts.

Addressing selection bias requires a conscious and deliberate strategy from cultural institutions. It involves actively seeking out and collaborating with communities whose histories have been underrepresented, allocating resources to preserve non-traditional materials (like oral histories or digital-born artifacts), and being transparent about the choices and limitations of their own collecting policies. Without this effort, the digital archive risks becoming a pristine, but profoundly incomplete, reflection of our world.

Creating a Disaster Priority List: What to Save First in a Fire?

The threat of catastrophic loss from fire, flood, or other disasters forces a brutal triage. Not everything can be saved, and a pre-defined disaster priority list is one of the most critical documents an institution can possess. Creating this list is not simply about identifying the most valuable items in monetary terms; it is a profound exercise in defining the core identity of a collection. It forces curators and archivists to ask: what objects are so essential that their loss would render the rest of the collection incomprehensible?

The process involves moving beyond individual object value to a more holistic, network-based understanding of the collection. A priority list should focus on “keystone” objects—items that provide essential context for countless others. This could be a founding charter, a unique scientific specimen, or the original negative of an iconic photograph. The irreplaceability of an item is a key metric. An object with no high-quality digital surrogate and no comparable counterpart elsewhere in the world would naturally rank higher.

The strategy must also be dynamic and scenario-based. A plan for a flood, which primarily threatens items on lower floors, will be different from a plan for a fire, where smoke and heat can affect an entire building. Zone-based plans that identify priority items within specific storage areas allow for faster, more effective response in a crisis. The goal is to create a clear, actionable framework that can be executed under extreme pressure, removing ambiguity when every second counts.

Your Disaster Triage Checklist: Prioritizing Cultural Assets

- Identify Keystone Objects: List all items that provide essential context or meaning to large parts of the collection.

- Create a Triage Matrix: Score items based on irreplaceability (e.g., unique primary source vs. published book) and informational density.

- Assess Surrogates: Prioritize unique primary source materials that have no existing high-quality digital or physical surrogates.

- Develop Zone-Based Plans: Create specific priority lists for different physical zones and tailor them to distinct disaster types (e.g., flood plan for the basement, fire plan for the main gallery).

- Implement Dynamic Adjustments: Build flexibility into the plan to allow for priority adjustments based on the specific requirements and constraints of an unfolding scenario.

Ultimately, a disaster plan is the ultimate expression of an institution’s values. The choices embedded within it reveal what that institution truly believes is essential, not just to its own identity, but to the cultural and historical record it holds in trust. It is the rawest form of curatorial decision-making.

Cloud vs. Hard Drive: Which Storage Lasts Longer than 10 Years?

For long-term digital archiving, the debate between local physical storage (like hard disk drives or LTO tapes) and commercial cloud services is often framed as a choice between control and convenience. Neither, however, offers a “fire and forget” solution. All storage media are subject to failure; the key is understanding their specific risks and lifespans to implement a strategy of managed decay. Hard disk drives (HDDs), for instance, are mechanical devices prone to failure. As industry endurance experiments reveal, annualized failure rates for disk drives can range from 3-10%, necessitating robust redundancy and backup strategies like the 3-2-1 rule (three copies, on two different media, with one off-site).

Cloud storage abstracts away the physical media, offering seemingly infinite capacity and professional management. However, it introduces new risks: provider failure, sudden price hikes, or data egress costs that can make retrieving large archives prohibitively expensive. You are trading direct control over the physical asset for dependence on a vendor’s business model and technical infrastructure. The lifespan of cloud storage is “indefinite,” but only as long as the provider exists and you continue to pay.

A more robust institutional strategy often involves a tiered approach that leverages the strengths of multiple formats. The following table, based on data from archival institutions, breaks down the trade-offs.

| Storage Type | Expected Lifespan | Primary Risk | Maintenance Required |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enterprise SSD | 3-5 years (continuous use) | Write exhaustion | Active migration every 3 years |

| HDD Archive | 5-10 years | Mechanical failure | Periodic integrity checks |

| LTO Tape | 15-30 years | Physical degradation | Climate control, periodic verification |

| Cloud Storage | Indefinite with active management | Provider failure, egress costs | Contract monitoring, redundancy |

As this analysis from archival experts like the Library of Congress shows, there is no single “best” medium. LTO tape offers the longest physical lifespan but requires significant infrastructure and climate control. The cloud offers flexibility but introduces dependency. The most resilient strategy is one of diversification and active management, where data is regularly migrated from aging media to new formats long before failure becomes a critical risk.

Why Traditional Varnish Turns Yellow on Renaissance Paintings?

The slow, golden yellowing of a Renaissance painting is a classic example of predictable, physical decay. It serves as a powerful counterpoint to the chaotic and often abrupt nature of digital loss. The phenomenon is not a mysterious ailment but a well-understood chemical process. Traditional varnishes, made from natural resins like dammar or mastic, were applied to protect the paint layer and saturate the colors.

However, these organic resins are inherently unstable. Over time, they react with oxygen and light in a process called oxidation. As conservation science demonstrates, this oxidation creates new molecular structures called chromophores. These chromophores are molecules that are particularly effective at absorbing light in the blue and violet parts of the spectrum. When blue light is absorbed, the light that is reflected back to our eyes is dominated by the remaining wavelengths—yellow and red. This is why the varnish appears to turn yellow, and eventually brown, obscuring the artist’s original palette.

The beauty of this type of decay, from a preservationist’s perspective, is its predictability. Conservators understand the chemistry involved and have developed methods to address it. A yellowed varnish can often be carefully removed and replaced with a more stable, modern synthetic varnish that is chemically designed to resist yellowing. This process is delicate and requires immense expertise, but it is possible because the underlying paint layer remains largely intact beneath the decaying protective coat.

This stands in stark contrast to digital decay. There is no “varnish” to remove from a corrupted file. The data itself is the artwork, and its corruption is often irreversible. The yellowing of a painting is a gradual dimming of information; bit rot is a switch being flipped to “off.” Understanding the predictable decay of physical objects helps us appreciate the uniquely fragile and absolute nature of digital preservation challenges.

Key Takeaways

- The primary archival challenge is not choosing between physical and digital, but actively managing the inevitable decay (entropy) of all media.

- Digital loss is often catastrophic and absolute (“bit rot”), while physical decay is frequently gradual and can be mitigated.

- Selection bias is an active threat; what is not chosen for preservation is erased from history before it even has a chance to decay.

- An object’s meaning is derived from its context (biography, history, metadata), and preserving this context is as crucial as preserving the object itself.

Separating Artist Biography from Artwork: When Does Context Matter?

The debate over whether an artwork should be judged independently of its creator’s life and character—the “art for art’s sake” argument—is an old one. However, in the realm of archiving, context is not an optional accessory; it is a fundamental component of an object’s identity. To remove an artwork from its biographical, social, and historical context is to strip it of much of its meaning. A portrait is not just a collection of brushstrokes; it is a document of a relationship between artist and sitter, a product of a specific cultural moment, and an artifact of a particular life story.

In a physical archive, this context is often stored separately: in catalog entries, artist letters in another collection, or scholarly books on a library shelf. The digital realm offers a revolutionary possibility: to fuse the object and its context together. Here, context becomes metadata, a layer of information that can be directly and permanently linked to the digital artwork file.

This integration of object and information is a core principle of modern digital curation. As experts from leading cultural institutions argue, this connection is not just a convenience but a fundamental shift in how we understand archival objects.

In a digital archive, context becomes fundamentally inseparable from the artwork. Biography, letters, and social history are not just adjacent information; they are layers of metadata that can be directly linked to the digital object.

– Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, Intangible Cultural Heritage Documentation

The question, then, is not *if* context matters, but *which* context to prioritize. The decision to link an artwork to a creator’s controversial political views, personal scandals, or, conversely, their revolutionary activism, directly shapes how future generations will interpret that work. Preserving these layers of contextual integrity is perhaps the most important archival task of all. Losing a file to bit rot is a tragedy, but preserving a file stripped of its meaning is a far more subtle, and perhaps more profound, failure.

For cultural institutions and historians, the path forward is clear. The focus must shift from a static obsession with finding a permanent storage medium to a dynamic, strategic commitment to preservation as an ongoing activity. This means embracing a policy of managed decay, investing in the integrity of metadata, and making conscious, ethical decisions about access and selection. The next step is to develop a holistic preservation policy that treats archiving not as a solved problem of storage, but as a perpetual and vital curatorial practice.