The critical debate isn’t whether to use an artist’s biography, but how to recognize it as just one of many interpretive layers—or ‘overpaints’—applied to an artwork.

- It reveals how trauma narratives can dominate an artist’s legacy, as seen with Frida Kahlo, often overshadowing formal analysis.

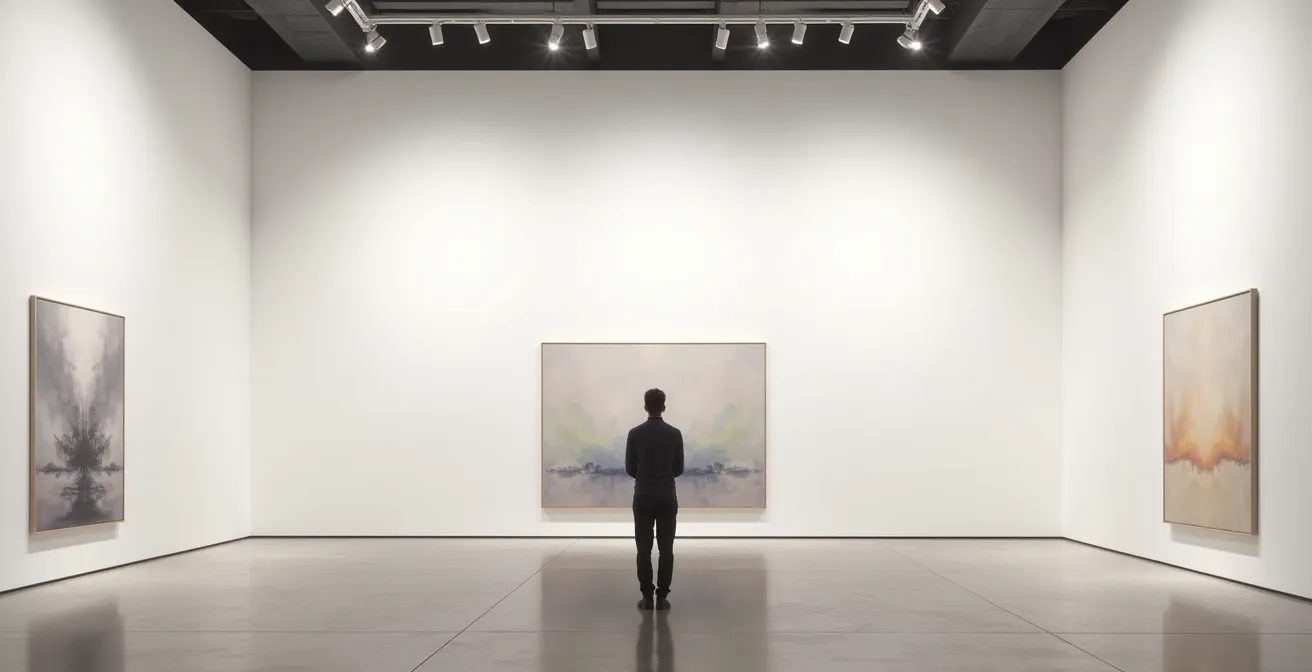

- It shows how institutional framing by museums and galleries shapes meaning before a viewer even sees the art.

Recommendation: Learn to critically identify and ‘strip away’ these contextual layers to engage directly with the work’s material and formal qualities.

For any art student or critic, the dilemma is both perennial and profound: how much should an artist’s life story influence our interpretation of their work? We are taught to revere the formal purity of the artwork, to heed Roland Barthes’s proclamation of the “Death of the Author,” and to let the piece speak for itself. Yet, we are simultaneously drawn to the powerful, often tragic, narratives of artists like Frida Kahlo or Vincent van Gogh, whose life stories seem to offer a key to unlock the emotional depths of their creations. This tension creates a critical paralysis, caught between the cold analysis of formalism and the seductive allure of biography.

The common approach is to see this as a binary choice: either the biography is the master key, or it is irrelevant noise to be ignored. We are told context is important, but rarely are we given the tools to dissect what “context” truly means. It encompasses not just the artist’s personal history but also their public statements, the historical moment, and the very way the art is presented to us by institutions. This article argues that the most sophisticated approach is not to choose a side, but to reframe the problem entirely.

Instead of a binary choice, we should view context as a series of interpretive layers—or “overpaints”—applied to the original artwork. The true skill of the critic lies not in ignoring these layers, but in learning to identify, analyze, and metaphorically strip them away to understand both the artwork and the forces that shape its meaning. This guide will explore the most common types of interpretive overpaint, from dominant trauma narratives and the artist’s own curated statements to the powerful framing of museums, providing a framework to move beyond the simplistic biography-versus-artwork debate and toward a more nuanced and empowered mode of interpretation.

Table of Contents: A Critical Look at Art, Biography, and Interpretation

- Why Trauma Narratives Dominate Interpretations of Frida Kahlo?

- How to Write an Artist Statement Without Sounding Pretentious?

- Intentionalism or Reader-Response: Which Approach Validates the Viewer?

- The Explanation Trap That Kills the Mystery of Abstract Expressionism

- Reinterpreting Colonial Art: The Shift from Celebration to Critical Analysis

- How to Remove Overpaint Without Touching the Original Pigment?

- The ‘Translator’s Voice’ Trap That Overpowers the Original Style

- How Color Theory Influences Buyer Emotions in Modern Art Galleries?

Why Trauma Narratives Dominate Interpretations of Frida Kahlo?

The case of Frida Kahlo offers a potent example of narrative dominance, where the artist’s biography, particularly her suffering, becomes the primary, and often sole, lens through which her work is viewed. Her art is inextricably linked to the bus accident, her tumultuous relationship with Diego Rivera, and her chronic pain. This biographical “overpaint” is so thick that it can be difficult to see the work underneath in any other light—for example, as a sophisticated exploration of Mexican identity, surrealist symbolism, or formal portraiture conventions. Academic discourse itself often reinforces this; as Romagna et al. note in the International Review of Psychiatry, a primary focus is understanding her “resilience in the face of lifelong trauma and chronic pain.”

This focus is so prevalent that even recent scholarship continues to center on these themes. For instance, a 2024 psychobiography study examining resilience factors in Kahlo’s art demonstrates an ongoing academic investment in this very narrative. This is not to say the narrative is false, but that its dominance can be restrictive. It pre-packages the work for the viewer, telling them what they are supposed to feel and see before they have had a chance to simply look.

Case Study: The Broken Column as Trauma Incarnate

Perhaps no work exemplifies this more than The Broken Column (1944). Here, the fusion of physical and emotional pain is made graphically explicit. The exposed, shattered column replacing her spine and the nails piercing her body are direct visual translations of her suffering. As her biographer, Hayden Herrera, describes, “A gap resembling an earthquake fissure splits her in two… The opened body suggests surgery and Frida’s feeling that without the steel corset she would literally fall apart.” The painting becomes a document of trauma, a piece of evidence, which can make it challenging to analyze its purely formal qualities without the biographical filter.

The danger for the critic is when this narrative becomes a substitute for analysis rather than a component of it. It creates an interpretive shortcut that, while emotionally compelling, can obscure the multifaceted genius and technical skill present in Kahlo’s oeuvre. The first step in a nuanced critique is to acknowledge this dominant narrative as a powerful layer of context, but not the only one.

How to Write an Artist Statement Without Sounding Pretentious?

If biographical trauma is an often-unintentional layer of “overpaint,” the artist statement is the artist’s own, deliberate application of an interpretive frame. It is a strategic tool, yet it frequently becomes a minefield of academic jargon, lofty claims, and biographical self-mythologizing that alienates viewers rather than inviting them in. The challenge is to guide the viewer’s entry point without dictating their entire experience. A successful statement shifts the focus from an opaque, ego-driven “who I am” to a more generous and grounded “how this was made” and “what it explores.”

The key to avoiding pretension is grounding the language in material honesty and tangible processes. Instead of declaring that the work “interrogates the liminal spaces of late-stage capitalism,” it is more effective and authentic to state that “this series uses reclaimed construction materials to explore the textures of urban decay.” The first is an unverifiable intellectual claim; the second is a verifiable, material fact that gives the viewer a solid starting point for their own interpretation. In this sense, a good artist statement functions less like a philosophical treatise and more like a map of the work’s physical and conceptual territory.

This strategic approach to writing can be broken down into several key principles:

- Frame the statement as a strategic tool to guide—not dictate—the viewer’s entry point.

- Shift focus from ‘who I am’ to ‘how this was made’ and ‘what it explores’.

- Ground the statement in tangible artwork and materiality rather than abstract biography.

- Consider the radical choice of minimalism or omission to force a direct confrontation with the work.

Ultimately, the most powerful artist statement might be the one that shows restraint. By focusing on process, materials, and open-ended questions, the artist respects the viewer’s intelligence and creates space for a genuine dialogue with the artwork itself, free from the “overpaint” of self-aggrandizement.

Intentionalism or Reader-Response: Which Approach Validates the Viewer?

At the heart of the struggle between biography and artwork lies the theoretical debate between Intentionalism and Reader-Response theory. Intentionalism, in its purest form, argues that the meaning of a work is determined by the author’s or artist’s original intention. To understand the art, we must understand what the artist *meant* to do. This approach heavily privileges the artist’s biography, statements, and letters as primary evidence. In contrast, Reader-Response theory posits that meaning is created in the act of reading or viewing; the viewer, with their own unique experiences and perspectives, becomes a co-creator of the work’s significance.

The most radical articulation of this latter view is Roland Barthes’s 1967 essay, “The Death of the Author.” For Barthes, to give a text an Author is to impose a limit on that text, to furnish it with a final signified. He famously argues that a text is not a line of words releasing a single ‘theological’ meaning (the ‘message’ of the Author-God) but a multi-dimensional space in which a variety of writings, none of them original, blend and clash. As he puts it, the text is “a tissue of quotations” drawn from innumerable centers of culture.

This concept is liberating for the viewer. It dethrones the artist as the sole arbiter of meaning and validates the viewer’s own interpretation. According to this framework, asking “What did the artist mean?” is an unanswerable and ultimately irrelevant question. The artist’s intentions are just one more piece of text, one more layer of “overpaint,” that has no more inherent authority than any other. The “author” who writes is no longer the same person as the one who lives and breathes, and their work does not contain a reliable record of their feelings or motivations.

However, while “The Death of the Author” validates the viewer’s agency, it does not mean that all interpretations are equally valid. A strong interpretation must still be grounded in the evidence of the artwork itself—its form, its structure, its materials. The theory empowers the viewer not to invent meaning out of thin air, but to engage in a rigorous dialogue with the work, free from the obligation to perform a biographical mind-reading of its creator.

The Explanation Trap That Kills the Mystery of Abstract Expressionism

Abstract Expressionism presents a unique challenge to interpretation precisely because it resists easy narrative. Without recognizable figures or scenes, the viewer is left to grapple with pure form, color, and gesture. This can be disorienting, leading to a desperate search for an “explanation” that can domesticate the work’s raw power. Often, this explanation is sought in the artist’s stated intentions, creating what can be called the “explanation trap.” This is another form of “overpaint,” where the artist’s words are used to foreclose mystery rather than open it up.

Mark Rothko is a perfect example. His own words about his work are powerful and frequently cited. The Metropolitan Museum of Art notes his clear artistic goal: “For Rothko, his glowing, soft-edged rectangles of luminescent color should provoke in viewers a quasi-religious experience, even eliciting tears.” This statement is immensely helpful as a point of entry, but it can also become a trap. A viewer, armed with this knowledge, might approach a Rothko painting with a checklist: “Am I feeling a quasi-religious experience? Am I about to cry?” If not, they may feel they have “failed” to understand the work, when in fact they have been prevented from having their own, authentic reaction.

The Abstract Expressionists themselves were often wary of this trap. They were deeply engaged with ideas, but they wanted the primary encounter to be visual and visceral. They created works on an immense scale, not for grandiosity, but for intimacy. As the Metropolitan Museum notes, the vast scale of the works was meant to envelop the viewer, making the confrontation with the painting a total experience. Rothko famously said, “I paint big to be intimate.” This physical, sensory engagement is what the work *does*, and it can be lost if we are too preoccupied with what the artist *said*.

Escaping the explanation trap requires a shift in the viewer’s objective. Instead of asking, “What does this mean?” one might ask, “What is this doing?” or “How am I reacting to this color, this scale, this texture?” This returns the agency to the viewer and to the direct, unmediated experience of the artwork itself, allowing its mystery to remain intact.

Reinterpreting Colonial Art: The Shift from Celebration to Critical Analysis

Perhaps the most politically charged form of “interpretive overpaint” is that applied by institutions to art from the colonial era. For centuries, paintings and artifacts collected or created during periods of colonial expansion were presented as neutral documents of history or celebrations of aesthetic beauty. The institutional frame—the museum labels, the catalogue essays, the very architecture of the galleries—actively stripped these objects of their violent or coercive contexts. This was a deliberate application of a celebratory “overpaint” that obscured the power dynamics at their origin.

In recent decades, a significant shift has occurred. Museums are now grappling with their role in this historical narrative, moving from celebration to critical analysis. This process involves adding new layers of interpretation that acknowledge the problematic histories of their collections. They are rewriting labels, mounting critical exhibitions, and, in some cases, repatriating objects. This decolonization process is an explicit acknowledgment that museums are not neutral warehouses but, as some critics have termed them, “theaters of power.” These institutions deploy cultural capital to shape attitudes and ratify the power structures that brought these objects into their collections in the first place.

This institutional shift is not just theoretical; it has concrete policy implications. A prime example is the Smithsonian Institution’s 2022 policy update. As Polar Journal reports, the new ethical repatriation policy was established to return items that were acquired under circumstances now considered unethical, even if legal at the time. This is a profound change, moving from a purely legalistic framework to an ethical one. It recognizes that the original “overpaint” of legal acquisition is no longer sufficient to justify possession. For the viewer, this means that the context provided by the museum is itself a subject for critical analysis. We must ask: Who is telling this story? Whose voice is missing? And what power dynamics are at play in this very display?

How to Remove Overpaint Without Touching the Original Pigment?

The metaphor of “interpretive overpaint” finds its most literal parallel in the art historical method of Formalism. Emerging in the early 20th century with critics like Clive Bell and Clement Greenberg, formalism proposed a radical approach: to understand a work of art, one must focus solely on its formal qualities—line, shape, color, and composition—and ignore all extra-visual context. In essence, formalism is a method for chemically stripping away the “overpaint” of biography, history, and narrative to get to the “original pigment” of the artwork’s plastic reality.

As TheArtStory explains, “Formalism was not interested in the contents of the work as much as analyzing the lines, color, and forms presented – a dissection of the way paintings were made and their purely visual aspects.” This method was particularly suited to the rise of abstract art, which had shed narrative content. However, the principles can be applied to any artwork. It is an exercise in disciplined looking. A formalist analysis of a Frida Kahlo portrait would intentionally disregard her biography and instead focus on her use of color to create emotional tone, the flatness of the picture plane, the compositional arrangement of symbols, and the quality of her brushwork.

This is not to say that the biographical context is meaningless, but rather that it constitutes a separate layer of inquiry. The formalist approach argues that before we can understand how Kahlo’s art relates to her life, we must first understand how it functions as a painting. We must analyze the “acute pictorial realism” and “psychological intensity” inherited from her photographer father not as biographical data points, but as tangible visual strategies visible on the canvas. This provides a crucial baseline. Once we have a firm grasp of the work’s formal structure, we can then, if we choose, begin to re-apply the layers of context and see how they interact with that structure.

Removing the overpaint, in this sense, is not an act of destruction but of clarification. It allows us to see the foundational choices the artist made as a painter, weaver, or sculptor. It is a way of honoring the craft of the work before engaging with the story around it, ensuring that our interpretation is built on the solid ground of visual evidence.

The ‘Translator’s Voice’ Trap That Overpowers the Original Style

Every layer of context—the biography, the museum label, the critic’s review, the artist’s own statement—functions as a form of translation. Each “translator” takes the raw, non-verbal language of the artwork and converts it into words, concepts, and narratives. The danger lies in the “translator’s voice” trap, where the interpretation becomes so loud and authoritative that it overpowers the original work. The viewer ends up engaging with the translation rather than the art itself. The critic’s most important task is to cultivate the ability to tune out these voices and engage in a “direct reading” of the work.

Developing this skill requires conscious practice and a specific set of critical tools. It is an active process of reclaiming one’s own viewership from the many well-meaning but often overbearing translators. It involves prioritizing the primary source—the artwork—above all secondary interpretations. This doesn’t mean ignoring context entirely, but rather controlling when and how it is introduced into the analytical process. The goal is to form an initial impression based on pure visual evidence before allowing external narratives to shape perception.

By consciously managing the influx of information, the viewer can identify the biases and perspectives inherent in each “translation.” You begin to notice the museum’s particular narrative slant or the critic’s theoretical hobbyhorses. This awareness allows you to treat contextual information not as objective truth, but as one perspective among many, which you are free to accept, question, or reject based on the evidence of the artwork itself.

Your Viewer’s Toolkit for a ‘Direct Reading’

- Visual Analysis First: Dedicate time to looking at the work without reading any accompanying text. Analyze its composition, color, texture, and scale. Form a preliminary hypothesis based only on what you see.

- Seek Primary Documents: If you do seek context, prioritize the artist’s own original writings (letters, journals) over critics’ summaries. This gets you closer to the source, though it is still a translation.

- Compare Critical Sources: Read multiple interpretations of the same work from different critics or historical periods. Notice where they agree and disagree; this will reveal their individual biases and the “translator’s voice” of their era.

- Look Without Narrative: Practice viewing the work and consciously setting aside any known stories about the artist or the subject matter. What is left when the narrative is gone?

- Question the Frame: Actively question the voice behind exhibition texts and wall labels. Ask yourself: Whose voice is this? What is their goal? Whose voice is being excluded?

This toolkit empowers the viewer to move from a passive consumer of interpretations to an active, discerning critic who can navigate the complex ecosystem of meaning that surrounds any work of art.

Key Takeaways

- The central challenge in art criticism is not choosing between biography and formalism, but learning to identify the various “interpretive overpaints” applied to an artwork.

- Dominant narratives (like Frida Kahlo’s trauma) and institutional framing (like in colonial art displays) are powerful layers of context that can obscure a direct analysis of the work.

- The viewer’s ultimate goal is to develop a ‘direct reading’ skill, using tools to analyze the work on its own formal and material terms before engaging with external context.

How Color Theory Influences Buyer Emotions in Modern Art Galleries?

After metaphorically stripping away the layers of biographical, intentional, and institutional “overpaint,” what remains? The answer lies in the artwork’s fundamental, material reality and its direct, visceral impact on the viewer. It is here that formal elements like color, scale, and texture reclaim their primary importance. In the context of a modern art gallery, devoid of explicit narrative, color theory is not merely an academic exercise; it is a primary driver of emotional engagement and, consequently, buyer interest. The emotional resonance of a piece is often carried almost entirely by its chromatic and compositional structure.

The work of the Abstract Expressionists, particularly the Color Field painters, provides the ultimate test case for this principle. With narrative and figuration eliminated, color is no longer just a property of an object; it *is* the subject. As Britannica’s analysis of the movement highlights, painters like Mark Rothko used large, flat fields of “thin, diaphanous paint to achieve quiet, subtle, almost meditative effects.” His soft-edged, shimmering rectangles are designed to be experienced, not decoded. The “meaning” is the emotional and psychological response generated by the direct confrontation with these immense fields of color.

The gallery context itself is meticulously engineered to heighten this sensory, emotional experience. The stark white walls, the strategic lighting, and the generous spacing all work to isolate the artwork, removing external distractions and focusing the viewer’s entire attention on the formal properties of the piece. As the Royal Academy has noted in relation to Abstract Expressionism, “the intensity of this encounter can be heightened by the way the work is displayed.” The gallery becomes a controlled environment for an emotional transaction mediated by color. For a potential buyer, the decision is rarely based on an intellectual understanding of the work’s historical significance, but on a much more primal question: “How does this make me feel?”

This demonstrates the ultimate power of the “original pigment.” While layers of narrative and context can enrich our understanding, the core of the aesthetic experience resides in the unmediated, sensory dialogue between the viewer and the work’s fundamental elements. It is this direct emotional impact, driven largely by color, that often proves to be the most compelling and valuable quality of all.

The ultimate goal for the discerning student and critic is not to arrive at a single, “correct” interpretation, but to become proficient in navigating these layers of meaning. By learning to identify the “overpaint” of biography, intentionality, and institutional framing, and by mastering the tools of formal analysis, you cultivate the freedom to engage with art on your own terms. Start today to practice this active, critical viewership to transform your understanding and appreciation of art.